Cartridge Breakdown: .223 Remington & 5.56 NATO

The Round That Began As A Military Cartridge Changed Rifles Forever

The .223 Remington, ubiquitous today as a small-to-medium game cartridge, a self-defense round, and the 5.56 x 45mm, the .223’s military brother, is the standard service rifle and carbine round of the U.S. military and NATO. That last one is important because while the .223 was first introduced to the public as a varmint round, it was developed for the battlefield, and specifically, for a new philosophy of what a “battle rifle” would be in a modern war.

The round had a broad introduction to the public and the military during the Vietnam War, where it gained several bad reputations, which were the result of bad components rather than the cartridge design itself. But the concept of a small, fast round worked and it has been in service for about 60 years now. Today, it is one of the most popular common-use cartridges in the world.

It was a rocky road to get here.

.223 Remington Specs

| Designer: | Remington Arms |

| Introduced: | 1962, Produced Commercially: 1964 |

| Parent case: | .222 Remington |

| Case type: | Rimless, bottleneck |

| Bullet diameter: | 0.224 inches |

| Shoulder diameter: | 0.354 inches |

| Base diameter: | 0.376 inches |

| Rim diameter: | 0.378 inches |

| Case length: | 1.76 inches |

| Overall length: | 2.26 inches |

| Primer type: | Small rifle |

| Max pressure (SAAMI): | 55,000 psi |

| Velocity: | 2,750 fps – 3,750 fps |

History Of The .223 Remington

After a bunch of Pentagon politics, while the military was issuing the new M14 select-fire rifle in .308 Winchester, the Army was already looking for a replacement in the mid 1950s for a number of reasons. The new philosophy based on firefight data from WWII and the Korean War called for the end of the long-range-capable .30-caliber battle rifle, because the vast majority of encounters occurred at medium distances.

The idea was that an intermediate cartridge that compensated for a small, light bullet with high velocity was the way to go caught on. It also allowed each individual to carry more rounds of .223 for the same weight. Plus, the recoil was extremely manageable, and accuracy was good thanks to the velocity.

Fairchild Industries, Remington Arms, and a team of engineers organized by the U.S. Continental Army Command began developing a new intermediate cartridge in 1957, while Eugene Stoner, of ArmaLite at the time, began working on scaling down his AR-10 designed from a .308 to the new small-caliber, high velocity (SCHV) that was being developed. Winchester Ammunition was also in the mix.

Stoner and Frank Snow of Sierra Bullets chose the existing .222 Remington cartridge as a starting place. The velocity goal was 3,300 fps, and they settled on a 55-grain bullet.

They worked up some hot test rounds that achieved velocity goals and punched a hole through a steel helmet, which was one of the criteria, but the chamber pressures were too high. Stoner needed to increase the case capacity to keep the pressure down but maintain the velocity they needed.

He got in touch with folks at Winchester and Remington about giving him some more room. Remington gave him a case they called the .222 Special. After a few rounds of testing, it was renamed .223 Remington. But everything still needed tweaking—the failure rate was still too high. For the moment, the military backed off.

In an infamous story, at a 4th of July picnic in 1959, Gen. Curtis LeMay of the U.S. Air Force informally tested out an early ArmaLite AR-15 paired with the new .223 Remington ammo. He was impressed and the demonstration resulted in an order for the rifles to replace the M2 carbines that were still being used by certain Air Force personnel.

Later that year, the AR-15 and the .223 went through a new round of testing at the Aberdeen Proving Ground and the failure rate was down to 2.5 per 1,000 rounds. It moved on to more extensive trials.

A marksmanship test in 1961 showed almost double the number of shooters were able to achieve an Expert score with the AR-15 versus the M14. LeMay placed a new order for 80,000 rifles, and these became the first M16s. In July 1962, the AR-15 chambered in .223 was recommended for adoption; in September 1963, the .223 Remington was adopted as “Cartridge, 5.56 mm ball, M193.” The next year, the AR-15 was officially adopted by the U.S. Army as the M16 rifle, with slightly different features than the Air Force rifles. It went on to become the army’s standard issue rifle and saw its first extensive use in Southeast Asia.

The original 5.56 had a Remington-designed bullet atop IMR4475 powder that pushed it from the muzzle at 3,250 fps with a chamber pressure of 52,000 psi.

On the civilian side, Remington submitted specs for the .223 to the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute, which we all know as SAAMI, in 1962. In late 1963, Remington introduced the Model 760 rifle, its first chambered in the new .223 Rem.

.223 vs. 5.56: What’s The Difference?

Up until 1980, the military called the .223 a 5.56 because it does everything in metric, and that’s what 0.233 inches converts to in millimeters. But that year, a new cartridge was introduced for military service: the 5.56x45mm NATO, or M855. It was not identical to the .223, but the differences are slight.

The external dimensions of the two brass cases are nearly identical and have nearly the same case capacity—they vary by about 2.6 grains. However, the shoulder profile and the neck length of the two rounds is different, and the 5.56 cartridge case is a bit thicker and heavier to handle higher chamber pressures without splitting. This extra thickness can also result in unintentionally high chamber pressures when using reloading data for .223.

If a 5.56 is loaded into a chamber meant only for .223, the bullet will be touching the rifling of the barrel, and the forcing is tight, which increased the pressure.

The original pressure for the .223 Remington in 1964 using DuPont IMR powder was 52,000 psi, according to the SAAMI books. When the switch was made to Olin Ball powder, that went up to 55,000 psi.

You’ll also see chamberings on rifles labeled .223 Wylde, which is becoming the standard for new rifles. The chamber specs were designed by Bill Wylde as an ideal chamber to fire both .223 and 5.56, which also increased the accuracy of the 5.56 NATO round.

.223 Remington Myths Dispelled

It Causes Huge Wounds Because It Tumbles!

This is just silly. Yeah, tumbling bullets cause large, unpredictable wound patterns, but if the .223 was for some reason designed to tumble, it wouldn’t be accurate at all.

This story comes from the large wounds observed in Vietnam caused by the relatively small .223 bullet. Any bullet will tumble when it hits flesh, because there’s more mass at the back of the bullet and that mass is still moving when the tip hits. However, the wounds in Vietnam were caused by bullet fragmentation caused by the bullet’s high velocity and construction.

Why The First M16 Rifles & .223 / 5.56 Ammo Didn’t Work

The M16 got a bad rep early on, and it turned out it had more to do with the 5.56 ammo than the rifle, and not the cartridge design, but the powder it used.

Stoner designed the .223 using a specific propellant. When the M16 went into production for the Army in 1964, the brass found out that DuPont couldn’t mass produce the IMR 4475 stick powder Stoner had used and specified for use with the M16. So, Olin WC 846 ball powder was used. It generated higher pressures and achieved a 3,300 fps muzzle velocity, but—and this is important—it produced much more fouling than the DuPont powder.

There isn’t much space between the inner workings of an AR — the tolerances are tight, especially compared to a rattle-trap AK-platform rifle. It doesn’t tolerate much dirt and grime, which is why there aren’t many ways for dirt and grip to get into the action, unless you dip it in mud with the chamber guard open.

But all that fouling from the ball powder jammed up the works far too quickly, and troops were seeing critical malfunctions that cost lives.

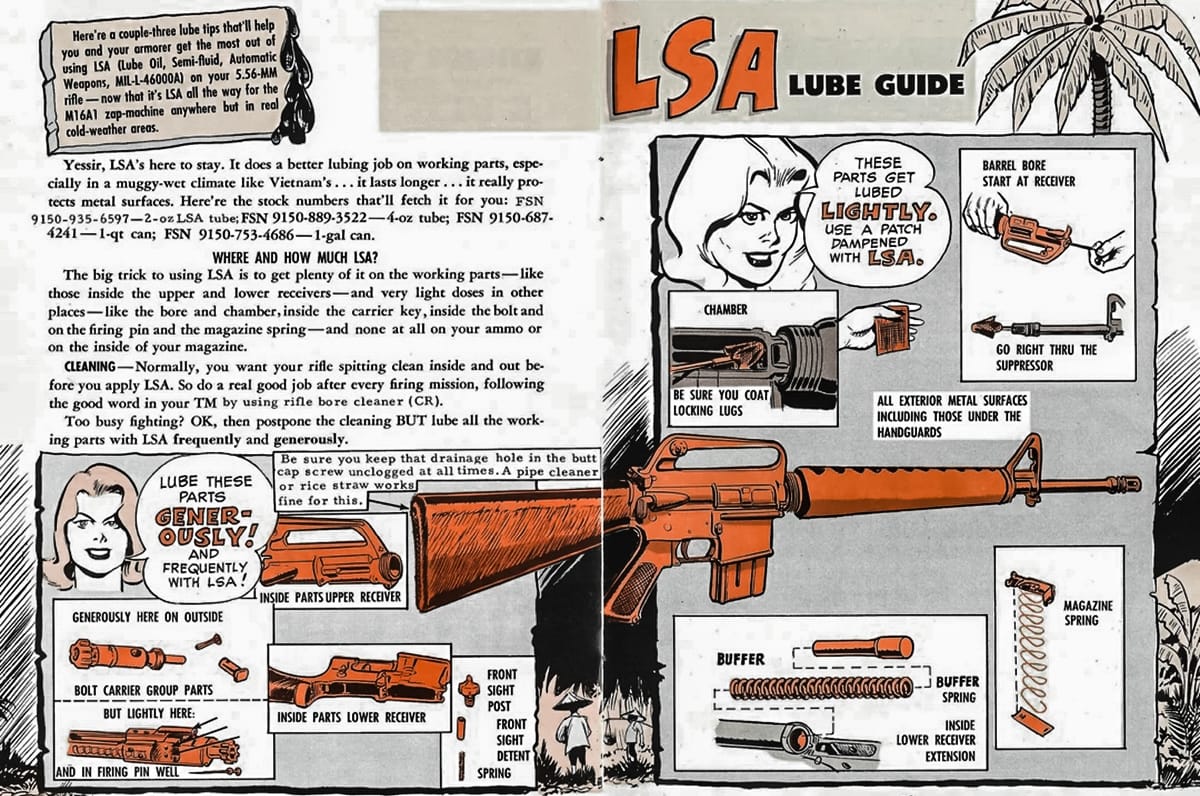

On top of all that, the first M16s, for some unknown reason, was billed by the Army as a “self-cleaning” rifle. They literally weren’t issued with cleaning kits of any kind. The military blamed Colt for saying it was low-maintenance, and Colt said low-maintenance doesn’t mean “self-cleaning.”

This, combined with the dirty propellant and the rifle’s unconventional construction and use of plastic and aluminum lead to a bad reputation from the start. It took many years for the platform to be fine-tuned and for that rep to be overshadowed.

The Army didn’t change the propellant it used. Instead, the M16A1 rifle had a chrome-plated chamber and bore to help reduce corrosion and the most severe and common malfunction seen with the M16, a failure to extract. The updated rifle was also issued with a proper cleaning kit along with solvents and lubricants, as well as an infamous comic book manual teaching soldiers how to care for the rifle.

The fix made the M16 and the .223 / 5.56 a far more reliable combination.