AR-10 Rifle History: Always A Bridesmaid

The .308 Version Of The AR-15 Came First But Finished Second

The AR-15 undoubtedly changed the course of firearm design, but it gets a bit of undue credit. Truly, it was Eugene Stoner’s earlier AR-10 rifle that truly ushered in a new age of rifle design.

It was simply built with few components that could be easily serviced in the field. An entire firearm could be assembled from a pile of parts or completely broken down with only a few simple tools, and it could be field stripped for cleaning and basic maintenance with no tools at all thanks to its receiver that was separated into an upper and lower with a removable bolt carrier group (BCG).

When Stoner, working for ArmaLite at the time, was building prototypes of a new concept rifle in the late 1950s, the U.S. military had committed to the new .308 Win/7.62 NATO cartridge for its new battle rifle, so that’s the cartridge he built his rifle around. He and the AR-10 design didn’t pivot until the military did. In fact, ArmaLite sent the AR-10 for testing by the U.S. Army before the AR-15 was even an idea.

AR-10 Development History

ArmaLite didn’t start out as a gun company, and Stoner didn’t start out as a gun designer, but here we are. So maybe it’s no surprise that the AR-10’s early years were fraught with stutter steps and a few embarrassing failures.

The company was founded by George Sullivan, who previously worked for Lockheed. It was funded by the Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation, of which ArmaLite became a subdivision in 1954.

There was a budget to work with and a small machine shop in Hollywood, California, of all places that would focus on small arms concepts — like an experimentation lab. The idea was that anything they created that was marketable would then be sold or licensed to actual gun manufacturers. The first project was building a lightweight survival rifle to be used by personnel of a downed aircraft.

The rifle became the minimalist ArmaLite AR-5 bolt action rifle in .22 Hornet. A semi-auto version was later created as the AR-7, which is still produced by Henry Repeating Arms. While Sullivan was testing the survival rifle at a shooting range, he randomly met Eugene Stoner, who dabbled in small arms but had a background in aircraft design.

Who Was Eugene Stoner?

In 1939, Eugene Stoner went to work as a machinist for Vega Aircraft Company, which later morphed into the Lockheed Airplane Company, and later the Lockheed Martin Corporation, but then came the war.

During World War II, Stoner served as a U.S. Marine working in the aviation ordnance department in the South Pacific and northern China. It was there he gained his earliest experiences working with high-caliber weapons and as an armorer. That, plus his combat training, no doubt helped him as a gun designer in later years.

When the war ended, Stoner began working in a machine shop for a small aircraft equipment company and later became a design engineer. That’s where he was exposed to materials like aluminum and modern lightweight, high-strength composites.

When Sullivan ran into him, Stoner had some interesting ideas about using some of those cutting-edge materials and production methods in a new kind of small arm design.

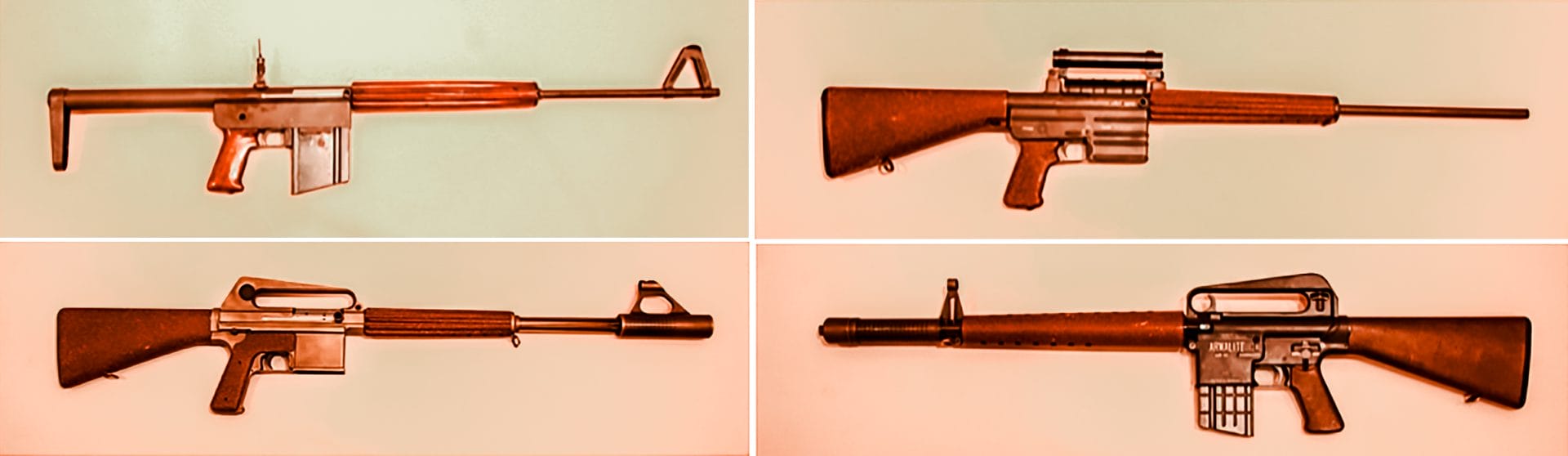

AR-10 Prototypes, The Hollywood Model & Testing Failures

Stoner became ArmaLite’s chief designer and began working on the .308/7.62 mm AR-10 through 1955 and 1956 as the Army was testing out replacements for the M1 Garand. The competition was Springfield’s T44E4 (which became the M14) and the Belgian FN FAL rifle, which was called the T48 at the time.

The AR-10 was a late entry and there were only two hand-built rifles and two prototypes submitted for testing at the Springfield Armory.

That final AR-10 prototype included some big advancements in Stoner’s design. It had the straight-line stock configuration, giving the rifle an overall in-line recoil absorbing design, elevated sights, an oversized aluminum flash suppressor and compensator, and an adjustable gas system, but it also had the now familiar hinged upper and lower receivers with takedown pins. The charging handle was still located on top of the receiver, but this latest version was non-reciprocating.

While it looked like a space gun for the time, it also weighed a paltry 6.85 pounds unloaded, something ArmaLite wanted to emphasize. It tested quite well at Springfield Armory and received favorable results, for a while. Sullivan insisted that an experimental aluminum and steel composite barrel be used for the tests over Stoner’s objections.

One of those barrels ruptured during a torture test in 1957. ArmaLite put on a conventional steel barrel, but the failure had ruined the AR-10’s chances in the trials. Also, there were plenty of internal politics going on and individuals and groups who wanted to see the M14 succeed.

ArmaLite decided the commercial market would be the way to go for the AR-10 and it produced a run of about 50 rifles for its sales agents to show off. They became known by collectors as the “Hollywood model.”

Slowly, the wild rifle design began to sell. ArmaLite sold a five-year manufacturing deal to the Dutch Artillerie Inrichtingen (A.I.), which had a large factory and production facility for any forthcoming orders.

A deal was set up for 7,500 AR-10s to be sold to Nicaragua with delivery beginning in early 1958. However, the rifle first had to pass a lengthy torture test.

The only rifle the salesman had to leave with the nation’s chief military commander, Gen. Anastasio Somoza, was his demo Hollywood model. He personally ran the rifle through its torture test, until the bolt lug over the ejector sheared off and flew past his face. The order was canceled and ArmaLite refitted the Hollywood models to prevent that from happening again, but once more, the damage had been done.

But ArmaLite fixed the issues, kept adding improvements, and made sales in limited numbers to various countries including Guatemala, Burma, Italy, Cuba, Sudan, and Portugal. The rifle had the greatest success in Sudan, where it was used by the nation’s special forces until 1985. These rifles were all manufactured by A.I.

Design Ins & Outs

At its core, the AR-10 is a light, air-cooled, magazine-fed, gas-operated rifle that uses a piston within the bolt carrier with a rotary bolt locking mechanism. It had an in-line stock, a revolutionary aluminum alloy receiver, and a fiberglass-reinforced pistol grip, handguard, and buttstock. None of that had been seen together in a rifle design before.

The bolt carrier group, or BCG, might be the most remarkable and underrated aspect of the rifle’s design. It acts as a movable cylinder while the bolt acts as a stationary pistol. This eliminated the need for a conventional gas cylinder, pistol, and actuating rod assembly, which simplified the firearm and saved weight.

Now, you might find it hard to believe that a man who had never built a gun from scratch before just came up with the AR-10 out of thin air — and you’d be right. And why should he? There was over a century of relevant firearms innovation to draw from, especially the firearms developed during WWII.

Stoner borrowed the hinged receiver idea from the FN FAL, and it could be argued that FN got that concept from the break-action shotgun. The ejection port cover on the AR is very much like the German StG44, which is often credited as the first assault weapon and the inspiration for the Soviet AK-47. The bolt mechanism on the AR-10 is not dissimilar from the M1941 Johnson rifle, which was an adaptation of the Remington Model 8 bolt designed by John M. Browning.

Where did the in-line stock layout idea come from? Check out the straight-line recoil configuration of the German MG 13 light machine gun, the FG 42, and, again, the M1941 Johnson. If it worked to control recoil in machine guns by reducing muzzle climb, why not a rifle?

Stoner took these ideas and blended them with modern materials to create a new kind of rifle that was accurate, rugged, and incredibly lightweight. And it also directly led to the creation of the most popular rifle platform ever made, the AR-15.

Scaling Down To 5.56

While ArmaLite was trying to sell the AR-10, the U.S. was gradually entering into a full-scale war in Vietnam, and the M14 was going down in flames.

The .308 rifle was essentially an updated, select-fire version of the M1 chambered in .308 — a cartridge designed to be an updated version of the .30-06 Springfield that was ballistically similar but could be used in a short-action rifle.

While the military’s old guard got its way and the M14 was adopted, the new guard, best characterized by people like Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara who took office in 1961, was data-driven. The data coming back from the field reports didn’t paint the M14 in a positive light, while at the same time, the philosophy behind a primary fighting rifle was changing rapidly — again, based on battlefield data.

The numbers said most military engagements occurred in fairly close quarters — meaning there was no need for every soldier to carry a rifle capable of long-range engagement. Essentially, the data said the .308 was overpowered for general issue and that a smaller, lighter, faster cartridge would be ideal, because it would still be effective at the distances of most engagements, and it would allow individuals to carry more rounds of ammo for the same weight. Plus, such a firearm would, theoretically, be more useful in full-auto.

Add to that lousy reports of the M14’s ability in the field, and the rifle’s days were numbered. It was select-fire, with the idea that it could be used in full-auto in a submachine gun role, eliminating the need for something like the M2 Grease Gun. It was one of the first rifles to prove that the .308 is not controllable during full auto fire. The 20-round mag didn’t help. Plus, the wood stock swelled and malformed in the wet, humid jungle climate, destroying accuracy. A fiberglass stock was later issued, but it was too late.

The military wanted to implement its new philosophy, and Stoner’s space-aged rifle was the platform that was tapped to do it.

In 1957, ArmaLite and Stoner scaled down the AR-10 design to the new .223 cartridge that Stoner designed with Remington. After some additional tweaks and a roundabout introduction to the military through the Air Force as a replacement for the M1 Carbine, the AR-15 was delivered and later adopted as the M16 rifle chambered for the 5.56 x 45 mm NATO by the entirety of the U.S. military.

But what about the AR-10?

By 1959, ArmaLite, which was going through financial problems, gave up on selling Stoner’s design directly and sold production rights for both the AR-10 and the AR-15 to Colt when the AR-15 got traction. Colt produced the first M16s, and many after that. It sold the rifle on the civilian market as the Colt AR-15, and it sold the AR-10 as well.

The AR-10 continues to be sold on the civilian market in a wide variety of configurations.

The AR-10 Today

These days, the AR-10 is produced in various forms by a variety of companies. Also, it should be noted that people will often label a rifle as an AR-10 if it’s an AR-platform firearm chambered for anything bigger than a .300 BLK, whether it’s a .308 or a 6.5 Creedmoor.

These rifles have all the features and controls people have gotten used to from AR-15s over the years, and they are built for a number of applications, usually precision shooting and long-range accuracy.

The AR-10 never got the widespread adoption or fame that its sized-down version did, but Eugene Stoner’s original rifle concept is still alive and kicking, and will be as long as the platform remains popular.